Green libraries week

It’s Libraries Week this week, and this year it’s branded as Green Libraries Week!

One of the great cross-sector library projects of recent years has been Green Libraries. Led by CILIP, with many partners, it has supported and funded projects across library services, shared best practice, organised events, and more. The Green Libraries Manifesto gives library services the opportunity to formally adopt shared principles around sustainability.

Despite this, no data has been published that would enable analysis on how libraries contribute to carbon emissions, such as building energy usage, book transportation and storage, staffing, or digital processes (both user and internal), etc. These are all things that can be collected and analysed in order to ultimately reduce emissions, and make services more sustainable.

Data can inform policies. There are plenty of library policies that could adjust to consider carbon emissions. Some library services insist on in-person book renewals, after relatively few online renewals. Does it make sense to insist users come into a library purely to renew a book? With an emphasis on reducing carbon, these policies would change. Although carbon counting is a very rough science, we need to start considering all the carbon generated from library usage.

Libraries clearly use a lot of energy. They will have their own transport that’s relatively inefficient, old buildings with all associated utilities, staffing that is primarily on-site (relying on transport), as well as providing a physical presence to many thousands of users, all of whom are generating carbon in getting to the library.

There is a danger that in taking a role of educating the public, but providing no data about themselves, libraries will look hypocritical. “Here is how you can increase bees in your garden. Oh, you want detailed data on our energy usage? None of your business!”

There also seem to be woolly claims about the sustainability of libraries. To the point where libraries claim to be carbon negative: reducing carbon emissions by usual activities. The theory is that for each book produced there is a carbon footprint. And if that book is loaned many times to many people, that’s a saving from each person buying the book individually.

Simple? Well, no. Borrowing a library book is different to buying a book. People who buy a book often need to have their own copy, the library is not a replacement for that. If people only intend to read a book and then not touch it again, they may buy it, but will often pass it on anyway, in ways that are more efficient than a library.

Library usage is often a different motivation, people get books out of the library that they want to read but not buy. Or know that they need to read once in a short period of time, such as for a book group or education. This is primarily additional reading (and a good thing!) but in effect is always additional carbon emissions rather than a saving.

There is also the awkward fact that libraries can often claim to increase book sales. A Forbes article on libraries boosting sales discusses some reasons, and there are plenty more, not least in helping many people get into reading in the first place. Getting people hooked on books is not a carbon saving.

These are not bad things, they are very good. But we can dismiss the idea of some kind of indirect carbon saving from libraries. If anything, library usage significantly increases book production and carbon emissions elsewhere. Libraries can’t go too far down that road - it’s hard enough to estimate and reduce direct carbon emissions, without trying to calculate indirect ones.

Does any of this really matter? Not in terms of the actions we need to take. Book shops have the responsibility of looking at the carbon emissions from selling books. Libraries have the responsibility of making savings from library service activity. But it’s dangerous to start with any preconception of being fundamentally sustainable. It could lead to lazy thinking that inaction is OK.

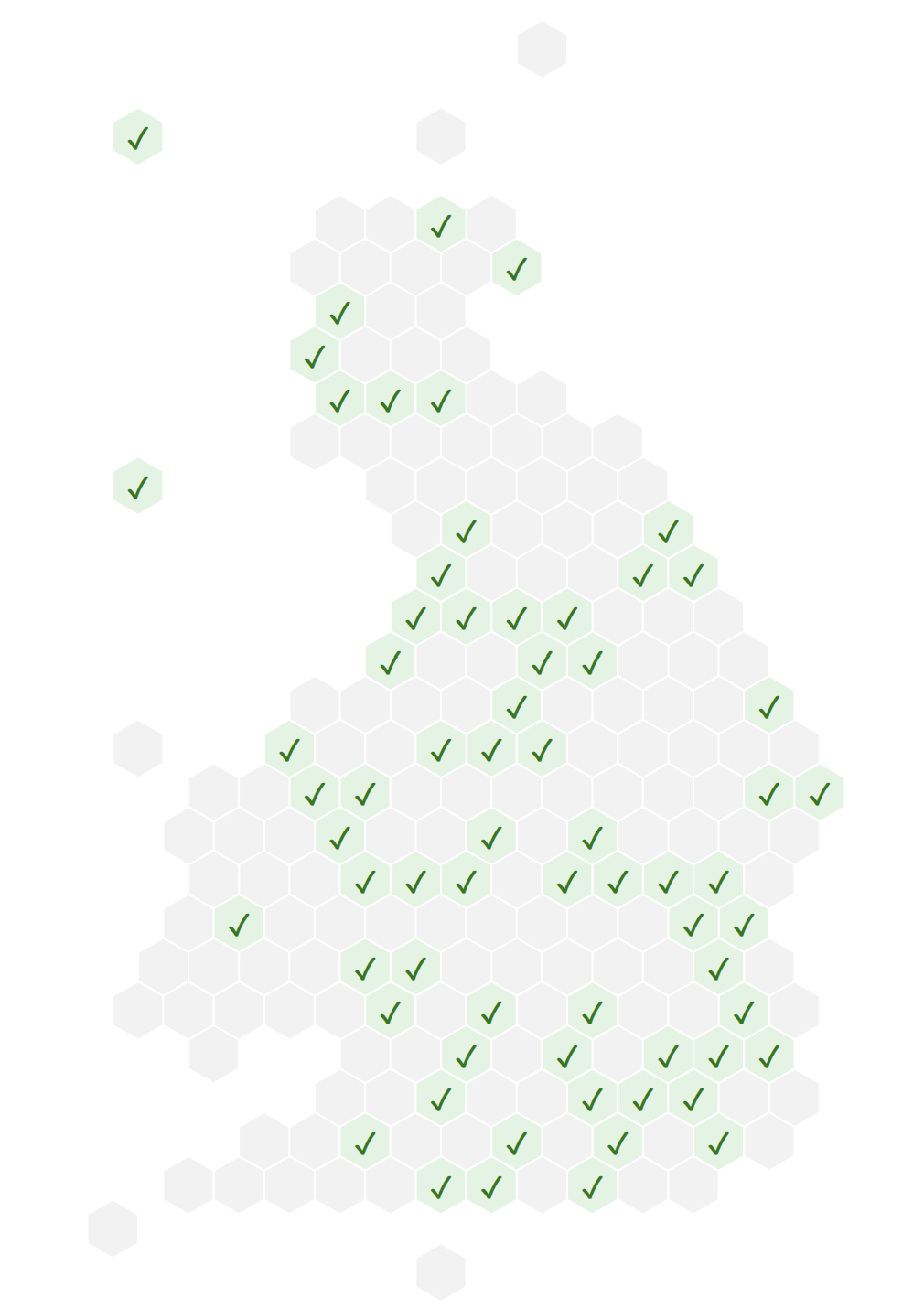

A small Libraries Hacked project, Green Libraries provides a visualisation of the (public) library services in the UK that have signed up to the Green Manifesto. But all digital projects have an associated carbon cost. The website carbon calculator provides a way of measuring the carbon impact of a webpage. The green libraries webpage is as minimal as possible, and estimated to be cleaner than 99% of pages tested. This Libraries Week we’ll be ensuring all Libraries Hacked projects are checked, and taking action to reduce their carbon footprint.