Missing libraries: towns in England without a public library

Where are the places in England that don’t have a public library? Well, there are loads, what does that mean? More clearly - where are the big towns without a library? Or, the towns that could really do with a library that don’t have one?

In 2018 a request was forwarded to Libraries Hacked from the Libraries Taskforce, then part of DCMS. A researcher was trying to find somewhere that didn’t have a public library, where having one would have a significant positive impact on the community.

This was shortly after the first Public libraries in England dataset, providing open data on library locations. That could be useful in assessing the current library network. It was also proposed that literacy data from the National Literacy Trust and Experian could help find areas in particular need of a library.

This has been on our project list for a long time, but other things got in the way. Also, the Experian/NLT data wasn’t appetising. It was at Ward level, and those are large and unwieldy administrative geographies. It seemed likely that detailed deprivation data would be required, which would then need to be matched to urban areas, as well as population counts to find areas of significant population. It seemed a task destined to sit on the back-burner.

However, The Library and Information Association (CILIP) recently announced an invitation to tender for a project called Future Libraries. It included this introduction:

The aim is to develop an evidence-based map of how current and future demand for library services is changing and provide a robust basis on which to plan and advocate for future development

CILIP Future Libraries

This seemed to be a similar analysis, but with a different focus. Demand is different to need - the CILIP project references future population and infrastructure. We have a library network which is outdated. Where population centres have changed, as well as shopping and work habits, the library network has remained static, aside from closures.

Regardless of future planning, it would be useful to go back to the original query, and look at locations without a library. We found the following open data sources:

- Libraries in England. Now published by Arts Council England (ACE), the latest is for December 2022.

- Built up areas. A 2022 dataset from Ordnance Survey (OS), representing Built Up Areas of Great Britain, designed to underpin statistical analysis.

- English indices of deprivation 2019. These are assessments of census-based areas to provide rankings of various deprivation measures.

- Census 2021. Data from the latest census, including population demographics at small census geographies.

Initial overview

The ACE libraries in England dataset is fairly straightforward to use. After filtering it to extract statutory and staffed public libraries, there are 2564 of these in England.

The OS built-up areas dataset “enables policy makers and analysts, both nationally and locally, to conduct analysis corresponding to actual urban extents, for example, at a town, city, and village level.”. In England there are 7091 of these. A slight flaw, for our requirements, is that it includes areas that are quite large e.g. Bristol. Bristol is a large enough city to need many libraries. The data is probably more useful for towns that aren’t part of a larger city.

Are all current libraries within a built-up area? Not quite - of the 2564 libraries, 6 were not. For example, Dent Library Link in Westmorland and Furness is in a location with a population of just 780. There’s nothing wrong with this - Libraries on the High Street research showed that public libraries appear in many different places, and shouldn’t be assumed to be urban. However, such areas are out of scope for this research, as we’re primarily looking at places of higher population.

Areas without a library

Population counts can be calculated for the built-up areas, using census data. The following are the 3 most populated built-up areas, that don’t have a library:

- Horndean, in Hampshire

- Chafford Hundred and West Thurrock, in Thurrock

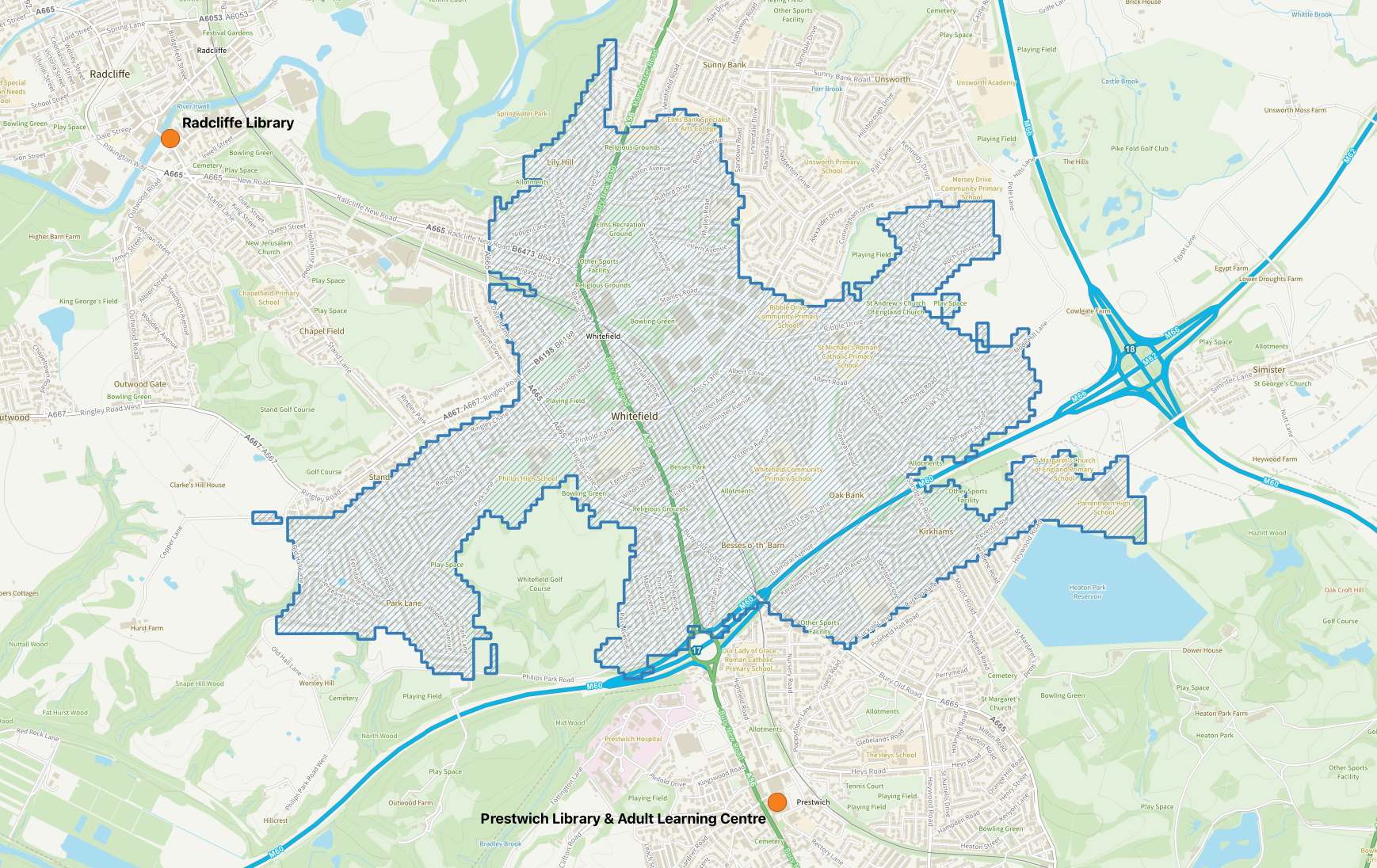

- Whitefield, in Bury

Research suggests these are feasible results. Horndean library closed in 2020, but there still seems to be a need for a library. A new community library has formed, independent from statutory provision. As an unfortunate indication of the value of the old library, the Rhymetime schedule is still listed on the NHS services directory.

A public library in Chafford Hundred was closed in 2011. Rented by the local authority from the school, it suffered from being stuck between political disagreements, poor opening hours, and was closed by the school, not the local authority. Chafford Hundred is a relatively new settlement, developed in 1985 for an initial 15,000 population, and has never had a truly dedicated public library.

Similarly, Whitefield. The library and adult learning centre in Whitefield was closed in 2017. A consultation report on the closure options highlighted that the area it served had a high proportion of young people, as well as a high level of deprivation.

Using this data

Those consultations and closures are done, and can’t be changed. But changes to the library network could be assessed on a national basis, as well as a local one. Is there a population threshold at which a settlement should have a library? We have a concept of this for schools and hospitals - they are referenced in the National Planning Policy Framework. Shared tools and data would be useful in assessing library provision. Consultations can be challenged, and be subject to oversight from the DCMS, but that doesn’t mean intervention will occur. Without established guidance on provision, it primarily comes down to ensuring consultations have been conducted properly.

One problem with consultations is that they often use current usage as a proxy for demand, which is short-term planning. Current usage is too easily misleading - affected by opening hours, variations in measuring usage, current service offer from the libraries, as well as marketing. The actual population count of an area has its flaws, but it indicates potential usage.

The House of Commons library published a report on the classification of towns and cities. It included specific levels of population to classify settlements:

Core Cities: twelve major population and economic centres

Other Cities: other settlements with a population of more than 175,000

Large Towns: settlements with a population between 60,000 and 174,999

Medium Towns: settlements with a population between 25,000 and 59,999

Small Towns: settlements with a population between 7,500 and 24,999.

Villages and small communities: settlements with a population of less than 7,500.House of Commons library. City & Town Classification of Constituencies & Local Authorities

These aren’t definitions of town/city using traditional status so some ‘large towns’ will have ceremonial city status.

Using these classifications, we can group the built-up areas, and see the proportion of each that don’t have a public library.

| Classification | % without a library |

|---|---|

| Cities | 0% |

| Large towns | 0% |

| Medium towns | 0.3% |

| Small towns | 11% |

| Villages and small communities | 90% |

It’s good to see that no city or large town is without a library, and almost every medium town has one. However, around 11% of small towns do not. As a large majority do, it is reasonable to expect a library in those places.

A data-informed library service standard could specify that small towns and above should all have a library. That would enable clear policy on what we expect from library provision. In practice, this would also not be too significant a change. There are currently 75 built-up areas with a population of over 7,500 that do not have a statutory and staffed library. It would not be a huge undertaking to meet that level of service.

For villages and small communities - as the majority do not have a library, there isn’t a clear suggestion that they should. But policies shouldn’t limit libraries in smaller areas - there would be many where it would be beneficial. Services such as mobile libraries and home library services should also cover areas where there isn’t a static library.

Areas in need of a library

In library consultations the idea of need is hugely important. A local authority has an obligation to prioritise citizens who most need their services. Who has greatest need of a library? People who can’t otherwise get hold of reading material. People who need the health outcomes from events. Those who don’t have digital devices and need to use the PCs. Maybe those who just need to stay warm in the winter.

But for long-term strategy, we all need libraries, and libraries need to appeal to everyone. That doesn’t mean that services shouldn’t assess libraries by the lifelines they provide. But any strategy should ensure they are accessible and appealing to all, to maximise usage and appeal.

In assessing need, it could be possible to come up with library specific indicators, such as literacy data. But the commonly used indices of deprivation provide perfectly good assessments across multiple deprivation indicators. These are income, employment, education, health, crime, barriers to housing and services, and living environment. Those are all problems in which it can confidently be said that a library service has a positive impact.

Census areas are assigned a single decile (from 1-10) to give them a multiple index of deprivation. A decile of 1 shows that a place is within the top 10% of most deprived areas. These communities tend to be smaller than towns, so a town may contain a variety of different deprivation assessments. There are different ways of aggregating deprivation within larger areas - one option is to assess each town by the minimum deprivation decile within it. It may be that only a small part of a town is at that level of deprivation, but it best represents the greatest need.

Of the 75 towns with a population over 7,500, there are 12 that contain communities with a multiple deprivation decile of 1.

Summary

- Open data on library locations and built-up urban extents can identify settlements that are not currently served by a statutory and staffed public library.

- Looking at small towns with a population of over 7,500, we can estimate that there are 75 without a library.

- Prioritising towns with high levels of deprivation, a shortlist of 12 could particularly benefit from library services.

Further developments

The data, code, and sources for the analysis will be released soon.

These insights should be available as interactive dashboards, rather than static reports. The OS Built-Up areas, alongside population and deprivation data, will also be available in the Libraries Hacked map tool at LibraryMap. This will allow all users and service professionals to explore different settlements and see aspects of missing library provision either nationally or in their local area.