Creating a library finder

A current Libraries Hacked prototype is Library Map, a search for public library locations in the UK.

It’s been getting more attention than usual. This is due to the work being done by LibraryOn, who have linked to it in their beta site. Hopefully, by providing an interactive element for users early on, they will gain feedback as to what people expect from that kind of service - and whether it’s something they should provide.

That attention has led to useful feedback for Library Map, and my own thoughts about what works, and what doesn’t.

We need this

People don’t know their local library has a website. They don’t know that mobile libraries exist. They dont know they can go on their Council website to see where (some of) their local libraries are, and if they did know they might struggle to find the information. Those libraries may be on the library catalogue site instead, linked to from the Council website under a title like ‘renew your loans’.

This is only known by people in the library sector, and those already engaged with it. To use library services online you need to know that it’s a bit of a mess, and that you’re going to have a tough time. That’s not a great situation, so we need tools and sites that bring information together.

It needs to be cross-authority

We treat finding your library the same as finding your bin day. And loads of people do that, right? Bin day lookups are the best and most popular web pages there are.

But you don’t need cross-authority bin day lookups, because only your local Council empties your bin. The same isn’t true of libraries. Many people have multiple library services relevant to them.

I go to Bath Library. It’s about 5 miles away, and there’s a direct bus from my house. But I live in Wiltshire. Because I’m a local government wonk, I know I need to go to bathnes.gov.uk to find out about libraries up the road, and wiltshire.gov.uk to find out about libraries down the road. But this isn’t obvious stuff that people know, it’s silly local gov stuff that people don’t know.

Imagine if you had to search all the different local councils around you to find out which one would empty your bin. There’d be riots. But we accept it in the library sector.

It needs mobile library stops

One of my bugbears is that on the rare occasion mobile libraries are listed alongside static libraries, the library van is listed (e.g. ‘North Mobile’). Vans are irrelevant to the public, who need information about stops. Mobile libraries are temporal entities that appear and disappear, and it doesn’t matter if behind the scenes there are two vans or a hundred. What matters is that a library will appear in the shade of the willow tree, between 11:00am and 12:00pm, every fifth Thursday of the month. Unless it’s broken down.

Mobile stop information can be impossible to find and interpret, even if you’re fortunate enough to be on the right website. It needs to be in a standard data format, and then integrated into library listings.

Distance is deceptive

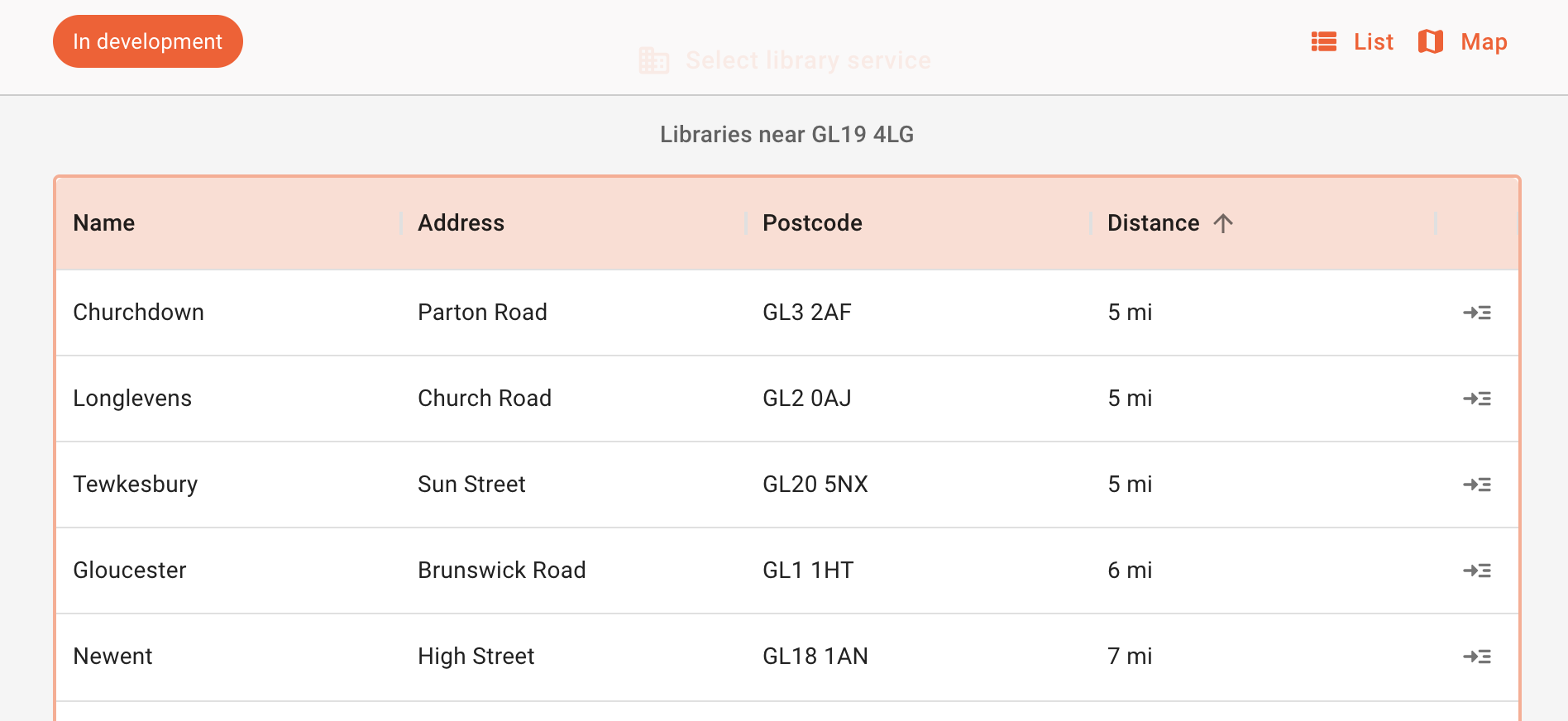

Library Map originally asked users to put in a postcode, and it would show libraries in that area, in alphabetical order. Simple? Maybe - but not what users expect. People expect to see the library closest to their postcode first.

In my own testing I’ve found distance to be unreliable, and it will cause situations I believe are worse than sorting alphabetically. A straight-line distance isn’t realistic enough to give a high level of detail, so it can only really be to the nearest mile. But in inner-London that can mean a whole set of libraries are all about a mile away. The distance then becomes useless, and including it only confuses listings. It’s also likely in these situations that geographic barriers will exist such as rivers, which mean a library is listed as closest but is the furthest away by actual travel distance.

In rural locations there are other problems. I tried my childhood home in Gloucestershire, and five libraries were returned. However, the closest two were irrelevant, as they were small branch libraries in the Gloucester suburbs. They weren’t places I’d know or be able to get to. The three relevant libraries were big town/city ones that I would recognise by name: Gloucester, Tewkesbury, and Newent. These are accessible by transport, and recognisable by name. Surely name is the most relevant thing to focus on?

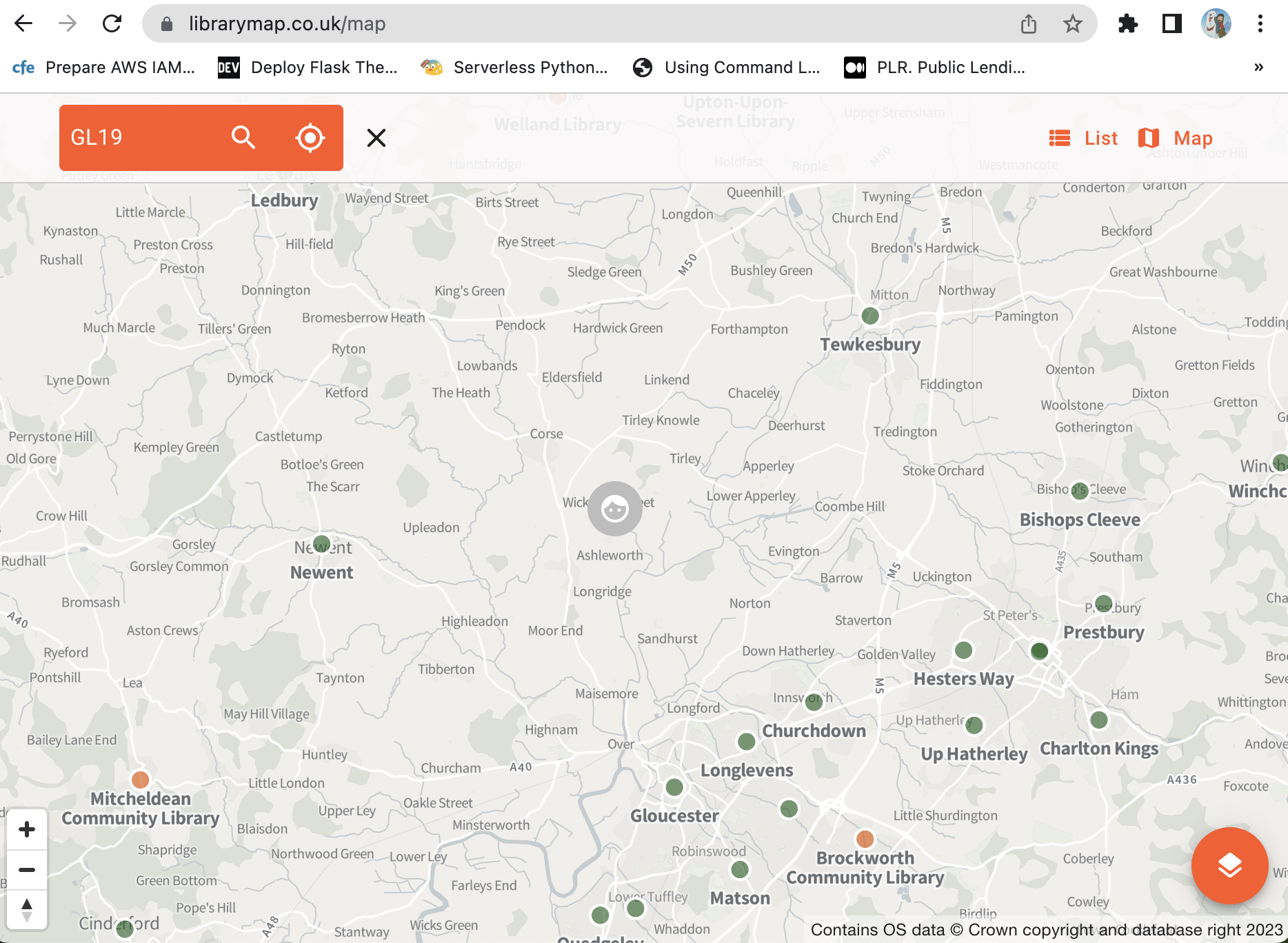

Anyway, matching user expectation is important, and the postcode search results are now ordered by distance. But, all of this is academic. Surely display the information on a map and people can see for themselves where the libraries are? Which leads to the next question…

Why is Library Map not a map?

I’m a geospatial software developer, so making digital maps is what I do. My first intention was to primarily make Library Map a map. Questions about sorting by distance would then go away. Also, maps are great.

However, prototype projects still need a grounding in reality, and unfortunately maps are not accessible. This is because they are visual rather than being text-based. Maps are exempt from accessibility legislation, but you still need to provide an alternative. I’d also say a map shouldn’t be the default way of presenting information.

Even beyond the obvious visual barrier, mapping software relies on people being familiar with map tools - zoom in, zoom out, pan, scroll etc. It’s an additional level of expertise that shouldn’t be assumed.

So yes, Library Map is not primarily a map. It’s mapping libraries in the sense of collecting library locations.

Surveying libraries is not enough

The data source for libraries in England is the Arts Council Basic dataset for libraries. This is completed by library services every December, and released as early as possible the following year.

The Libraries Basic Dataset is intended to capture permanent instances of libraries, local history libraries, and archives from 1 April 2010 to 31 December 2021. It is also intended to capture the number of mobile libraries.

Arts Council England

It’s now April 2023, and about 16 months out of date, but the next iteration should be released soon.

The Arts Council dataset does what it says it does. It captures libraries at a certain point in time. Best described as a series of ‘snapshots’, it is always correct, but never up to date.

The problem is, if you’re displaying current libraries, a survey doesn’t work. You can’t say ‘well, this was correct in December 2021’. People are looking for their local library right now.

Library locations should be maintained as a data register that is always up to date and the most reliable source of information. There are two ways of doing that:

- Let library services maintain their data and publish it in a standard format. I personally think this is the best, but it’s by far the most difficult to get everyone to do.

- Provide an interface for library services to update their data when they need to. This is OK, but it takes data publishing out of the hands of library services. This makes it a boring data-entry task for them to do on someone else’s system. Data publishing is important for services to do themselves, and get involved in. The bigger picture in library services is to enable open data publishing across a range of datasets.

An alternative may be adopting an existing data platform like Wikidata or Open Street Map, but libraries would have to accept anyone being able to update the data.

Bad data is good

Lol, what? Good data is good, bad data is bad.

Library Map has functionality to display opening hours and a web link to each library, but the data was getting very wrong. Even the Arts Council dataset no longer includes these things.

So, I made a decision to turn off web links and opening hours.

It’s better, probably, that people aren’t presented with wrong information. Maybe. But I wonder whether that was the right decision. There are two ways to react to invalid data about your libraries:

- That’s terrible, you can’t tell people things that are wrong!

- Ah, that’s out of date, how can we update that?

If you remove data when you’re no longer confident about it, you end up with no data. Big sites like Google know this, with products like Google Maps. They don’t want a poor user experience, but they’ll definitely display data they know is likely to be wrong. It draws attention to it, which makes it more likely to be fixed.

People raising data quality issues highlights the need for permanent data maintenance.

Developers are not interaction designers

I quite like terrible user interfaces. But that’s because I like data. So what better way of presenting libraries than in a data grid, with sortable columns, paging, and a custom filter for location or local authority? It’s like a spreadsheet! I’d also quite like a CSV download button.

This isn’t the best experience or service design for users. I have a feeling that a stepped approach would be better. Rather than starting with a table of all libraries in a data grid, maybe it should start with a clear process to enter your postcode, or even better, a place name. And then present results in a more friendly way, that incorporates both library name and distance appropriately.

But that’s beyond my expertise, and that’s OK. However, it was good to see the British Library recruiting for an Interaction Designer role as part of the LibraryOn team. Whatever digital services that’s for, it’s good to see the wider team growing and including wider skills.

Data needs applications

A final thought - it’s been really interesting to get feedback and thoughts from library services and other individuals.

It was always inevitable that as soon as data was made visible, within a practical application, libraries would take more interest in it.

I advocate for a ‘data-first’ approach: publish all your data, and more use will be made of it. But that’s a tough ask. In reality we need to build things first (even with bad data), and then get libraries improving data.